Alevism in Munzur

Sitting in the shade of a leafy tree near the springs at the source of the Munzur River, Hayri Dede, a highly-regarded Alevi religious leader, explains: “We do not believe we are going to Paradise after we die. For us, Paradise is the life we are living now. For us, Heaven and Hell are here on this earth.”

Zeynal Dede, one of the most beloved and respected pirs in the upper Munzur Valley, agrees. When he sings a dirge at a funeral, he says, the song is not really intended to benefit the dead person, but is instead meant for the living. “Its real purpose is to make us contemplate our own mortality and encourage us to live better, more ethical lives,” he explains. “It’s pointless to worship material things, because one day you’ll be dead and nothing that you own will matter any more. So the best thing is to be kind and just and generous to other people, because if in this world you are helpful and loving, then you are already living in Heaven. But if you are greedy and mean and dishonest, then you are living in Hell, here and now.”

Click ‘play’ to see Zeynal Dede play a funeral dirge

Kindness, generosity, open-hearted acceptance of others, treating people and the world itself with love – this is the ethos and the daily practice of Alevism – what’s called “the rule of the yol” – the Alevi path. Though it sounds like a remix of the Golden Rule, it’s not simply about doing unto others as you'd like others to do unto you; it’s about doing unto others as one should do unto God, since Alevis recognize a living spark of God in everyone. Acts of kindness and generosity are truly spiritual acts, through which Alevis connect to the divine.

Remarkably, these are not just abstract ideals that people in Munzur agree with in theory, then ignore. To the contrary, they have been absorbed into the culture, like indigo into cloth. They permeate many people’s way of being, and are expressed in ways that are completely natural and entirely authentic. Of course Munzur is not a little utopia filled with perfect, enlightened people – but it’s impossible not to sense the genuine warmth and kindness that flows from and between so many people, in a way that is effortless and organic, and not at all artificial, cynical, or contrived. Even in prayer, the Alevis of Munzur first pray for the well-being of the world, then they pray for the benefit of other people, and only finally, if at all, do they pray for anything for themselves.

In the dedes’ descriptions of Heaven and Hell, much is revealed. First, we see that Alevis are very comfortable with metaphorical interpretations and symbolic, rather than literal, truths; for them, neither Paradise nor the Inferno need to be actual places – instead, they are understood as states of being. It’s also clear that that the spiritual goals of Alevism are meant to be attained in this lifetime, not after death, and that there are choices to be made. Choose wisely, follow the Alevi path, and you may live your life in Heaven; abandon the path and you will dwell in Hell on earth.

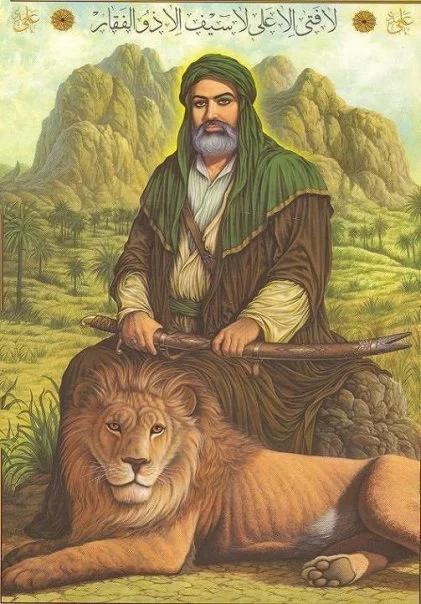

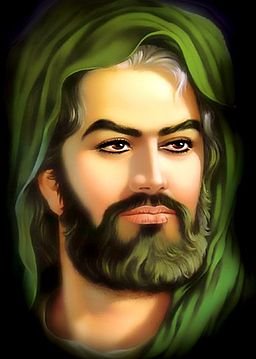

Alevism is often defined as a mystical, or syncretic, or heterodox form of Islam, and it’s easy to see why. Alevis regard Mohammed, the Prophet of Islam, as a saint, and have even greater reverence for Ali, the cousin and son-in-law of Mohammed, who became the fourth caliph of the Muslim world and remains the primary figure in Shia Islam. Alevis remember the slaying of Ali’s son, Husayn, at Karbala, as a catastrophe – as all Shia and many Sunni Muslim communities do – and numerous elements of Islamic myth, symbol, and history are inseparably intertwined with Alevi beliefs and practices.

Ali ibn Abi Talib

Husayn ibn Ali

The people of Munzur, however, tend to reject the notion that their religion is a branch of Islam. It’s not uncommon for locals to declare to outsiders, “We are not Muslim!” in a pre-emptive effort to clear up any possible confusion about who they are or what they believe. In part, this is because Alevis have long been discriminated against by Turkey’s Sunni Muslim majority, and the people of Munzur have no desire to be mistaken as belonging to a group that looks down upon them and their faith. They also feel that being categorized as Islamic is a fundamental misrepresentation of Alevism, betraying both the essence and the history of their religion.

Other communities of Alevis in other parts of Turkey feel differently about this. Some declare that Alevism is a purer, more truly Turkish form of Islam than the Sunnism imported from Arabia. Others emphasize their connection to Islam as a way of legitimizing their alternative faith in the eyes of Turkey's Sunni mainstream; in reaction to this, it's not unusual for some of the more outspoken residents of Munzur to voice the opinion that Alevi groups that identify as Muslim are selling out to Turkey’s Ministry of Religion / Directorate of Religious Affairs, which has the ability to channel substantial sums of money to communities – and individuals – that it views as allies.

The Alevis of Munzur trace the origins of their faith to ancient Zoroastrian and Shamanistic traditions that pre-date Islam by many centuries, and claim that the infusion of Islam into their religion occurred as a result of forced conversions at the hands of Muslim armies. Their ancestors, they say, had to give their religion a make-over, so that it looked on the surface as though its practitioners had adopted Islam, while at the core remaining true to itself. Any stories that point to Islam as the source of their unique practices, they claim, are apocryphal, invented so they could continue performing their sacred ceremonies under the thin guise of being faithful Muslims.

In fact, the history of the Alevi religion is clouded in vagueries. It appears to have evolved as a blend of Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Shamanism, Sufism, and other mystical traditions, with some elements eventually incorporated from gnostic interpretations of Shi’ism and Christianity.

The forced conversions to Islam referred to by the people of Munzur most likely happened around the dawn of the 16th century. During the 1400’s, much of eastern Turkey and northwestern Persia was ruled by a Sunni tribal federation known as the White Sheep Turkomans. Western Turkey was ruled by the Ottomans, who were also Sunni. But there were numerous groups in those areas, like the Alevis, who shunned Sunnism in favor of more ancient and mystical beliefs. One of these was the Safaviyya, a Sufi order that was founded in Azerbaijan by a Turkoman sheikh.

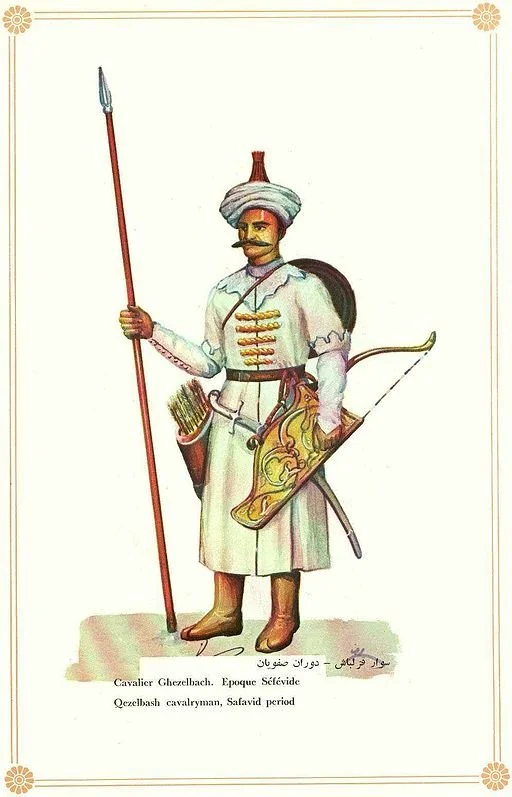

A Kizilbash soldier.

For twelve years, the Alevi Kurds of eastern Anatolia lived under the rule of the Shah. Then, in 1514, after fierce fighting, Ottoman forces captured most of eastern Turkey. The Alevi Kurds, thus, found themselves cut off from the Persian Safavids and in lands controlled by Ottoman Sunnis. The Ottomans assumed that all Alevi Kurds were affiliated with the enemy armies of the Kizilbash, and unleashed brutal reprisals against them. Many of the Kurdish Alevi tribes thus retreated into the mountains, where they were safe from attack.

Their isolation from Istanbul meant that Alevi Kurds could remain insulated from the dominant Ottoman Sunni culture. Their separation from Persia meant that, while Shia Islam became much more conservative, Kurdish Alevism was able to retain its mystical traditions, beliefs, and characteristics. In the early 16th century, Alevis might have thought of themselves as kindred spirits to the Shia; today, the Alevi Kurds – who are still known as Kizilbash – think of Iranian Shiites as “fanatics” and do not want their religion to be associated with Shi’ism at all.

When the Safaviyya asserted territorial ambitions in the 15th century, it began to recruit fighters to its side. Those armies wore turbans with distinct red peaks, and thus came to be known as “Kizilbash” – meaning “red headed” in Turkish. Alevi Kurds joined with the Kizilbash, partly because Alevism was much closer to heterodox Sufism than it was to orthodox Sunnism; also, times were tough, economically speaking, and the Kizilbash paid.

In 1502, the Safaviyya leader, Shah Ismail I, with great help from the Kizilbash, defeated the White Sheep Turkomans, went on to conquer and unite all of Persia, and founded the Safavid Empire. Shia Islam was declared the state religion, and everyone living under Safavid control was forced to convert to it under threat of death – including those in eastern Anatolia. At that time, Shi’ism had a more metaphysical and heterodox interpretation than it does today, and the Kurdish Alevis didn’t have to radically alter their religious practices in order to survive.

It should be noted that there are two main branches of Alevism – Kizilbash and Bektashi. When most people think of, write of, or study Alevism, they are focused on Bektashi - while here we are focused on the Alevis of the Munzur Valley, who are Kizilbash. Though many of the beliefs and practices of the two groups are very similar, the Bektashi are distinctly descended from the spiritual lineage of the great mystic, Haci Bektash. The connection that the Kizilbash have to Haci Bektaş is not exactly clear: most tribes regard him as one saint among many, but not as the founder of their faith. In general, the Bektashi Alevis tend to be Turkish while the Kizilbash are Kurdish (or Zaza, as some in Dersim self-identify). The Bektashi are more likely to claim a connection to Islam, in part because of important historical relationships between their tribes and the Ottomans, as well as the reality that for centuries they have lived in closer contact with the Sunni majority. The Kizilbash / Kurdish Alevis, on the other hand, are more likely to flat out reject any suggestion that they are Islamic – though these divisions are not absolute.

Haci Bektash

An important difference between Bektashi and Kizilbash Alevis is the influence of Armenian Christianity on the culture and beliefs on the Kurds of Dersim. For centuries, Armenians had a strong presence in the region. Some adopted Alevism in the 16th century, during the period when the Persian Safavids ruled eastern Anatolia and imposed Islam as the state religion. Since Alevism is such a heterodox faith, Armenians were able to maintain many of their practices, which became incorporated into Kizilbash Alevi customs.

During Ottoman times, as Armenians were even greater targets for persecution than the Alevis, more Armenian Christians gradually became Alevi. This phenomenon culminated during the Armenian Genocide of 1915-18, when 800,000 to 1.5 million Armenians were exterminated in all manner of horrible ways by the Ottoman state.

Though Sunni Kurds frequently participated in atrocities committed against Armenians in eastern Turkey, the Alevi Kurds refused to join in, and are known for protecting the Armenians during the so-called Great Crime. According to the German vice-consul in Erzurum during World War I, "the Kurds from Dersim...turned out to be the most important saviors of the persecuted Armenians. They organized regular escape roads to Russia, which, in the following period, particularly in the 30’s, led to their own annihilation by the Turks.” Alevi Kurds also sheltered the Armenians living in Dersim, covering up for the Christian families that stayed in the area and pretended to be Alevi themselves. Today, many crypto-Armenians from Dersim are beginning to re-claim their Armenian heritage.

Since Armenian traditions had merged into Alevism centuries earlier, the Armenians remaining in Dersim were easily absorbed into Alevism. It has long been said that "less than the thickness of an onion skin separates the Alevis and the Armenians." Such a smooth transition would not have been possible were the Alevis practicing a religion that resembled Sunni or Shia Islam. In fact, the differences between Alevism and Islam are profound.

Alevis in Munzur do not read the Koran. They reject the fundamental “pillars” of Islam, including the Ramadan fast, the Haj to Mecca, and the obligation to pray five times a day. When Alevis do pray, they don’t do it in mosques; in fact, in the town of Ovacik, the lone mosque is visited only by people who are not from the valley: policemen, soldiers, and some students who have come to attend the local college. When the call to prayer is broadcast, it’s not unusual to see a look of scorn cross the faces of some locals, who feel the mosque has been imposed upon their community by the Turkish government – which also forces their children to study Islam in school, even though it contradicts what the children are taught at home.

One of the few rituals shared by Muslims and Alevis is male circumcision. Here, five-year-old Serhat Yerlikaya is dressed up for photos that will grace the invitation to his circumcision ceremony.

While virtually all aspects of a faithful Muslim’s life are guided by the precepts of Sharia law, Alevis disregard Sharia as a rigid, and essentially useless, list of rules and regulations that they have no duty to follow. They believe there are four gates through which people have to pass on their journey toward God, and that Şeriyat (Islamic law) is the very first. After that comes Tariqat – ‘the path,’ which according to anthropologist David Shankland is “the inner way of the heart into which Alevis are born;” Marifet, or knowledge, an esoteric understanding of the divine; and Haqiqat or ultimate truth, which is the kind of union with God that’s achieved only by saints. For Alevis, Sharia laws can be seen as a kind of spiritual training wheels, which perhaps serve a purpose for those who can't stay upright without them, but which tend to get in the way when trying to actually go anywhere.

Alevism is focused on batın – the inner world of hidden meanings where spiritual truth is revealed – not zahir – external, surface appearances. For those who are on the path of batin, the do’s and don’ts of Sharia serve no purpose. What’s important to them is inner spiritual growth, not outward displays of faith or strict adherence to a litany of rules. While there are a core list of do’s and don’ts that Alevis are expected to obey, such as not stealing, murdering or committing adultery, the emphasis is, above all else, on treating other people, and nature, with love and respect.

As they see the presence of the divine in human beings, the Alevis of Munzur also see it in the natural world. “Nature is holy,” is a refrain commonly spoken around the valley, and everything in it is believed to have a soul, from animals and plants, to rocks, dirt, and especially water. Among the countless sacred sites scattered in and around Munzur, all are outdoors, in nature. Many are minor, such as special trees or boulders where people go to pray, which are known only to residents of certain villages. Other, more significant and widely-known sites, called ziyarets, tend to be major geographical features, such as mountains, rivers, and caves.

Alevis tie bits of string to sacred rocks and trees, symbolizing their prayers.

The Munzur River is particularly sacred, and its source is one of the holiest places of all. Alevis go there to light candles, to pray, and to cleanse themselves spiritually in the bracing waters that pour out of the base of a towering massif of the Munzur Mountains. Newlyweds include a visit to the springs as part of their wedding festivities, as lighting candles there is said to ensure a long and happy life together. Munzur Baba - as the source is often called - is also a very auspicious place for ritual sacrifice.

Above: A newly married couple visits the source of the Munzur with their wedding party.

Alevis bring sheep and goats to a rise above the water, where a cement pad with a blood gutter sits beneath a tin roof. One by one, the animals are led into the shelter, prayers are recited, and the slaughtering is performed, swiftly, by professional butchers. Once the carcass is skinned and dismembered, families take the meat down to the river, where they grill it or stew it, then serve it as part of huge feast.

The most important part of the slaughtering is not the blood offering itself – rather, the sharing of the meat with other people is what gives the ritual its potency, is what truly puts the sacred in the sacrifice. In summer, when the banks near the source of the Munzur are often thronged with picnicking families, the atmosphere is truly festive. People relax under shade trees, play music on the river banks, splash and swim in the holy water, and eat together with family, friends, and strangers. It seems like a form of recreational devotion – and it makes perfect sense, considering that that the goal of the Alevi religion is not an external display of piety, but experiencing an internal spiritual connection. What better way to achieve that, one might ask, then by spending a day in a beautiful natural setting and eating good food with loved ones, enjoying life’s simplest yet most profound blessings?

For Alevis in Dersim, the springs are as important to visit as Mecca is to Muslims (though there’s no religious obligation to do so). In fact, according to anthropologist Dilşa Deniz, the story of Munzur the miracle-working shepherd was created to counter Sunni pressure on Alevis to make Haj. When the agha who has just returned from his pilgrimage tells the crowd of people that Munzur is the one who deserves to have his hand kissed, the story is really saying that the springs are even holier than Mecca. In this way, it validates the Alevis’ disregard for the Haj, while elevating their own ziyarets to Mecca-like status. “It says, ‘Our Haj is here,’” Deniz says.

Many ziyarets are imbued with the stories of local saints and miraculous happenings. One, called Belhasan, is the highest point on a mountainside that rises behind Ovacik. To the south, the entire upper basin of the Munzur Valley unfurls, far, far below; to the north, jagged limestone ridges recede into the rugged heart of the Munzur range. It’s said that, long ago, a shepherd named Belhasan spent summers in the high meadows with his flocks. His brother, on the other hand, left the Munzur Valley to move to the city of Erzincan, where he worked as a shoemaker. After years of separation, Belhasan thought of his brother, and missed him greatly. He’d had no news from him in ages, and wondered if he was still alive and well.

“I must go and visit him,” Belhasan said to himself, and began musing about what kind of gift he should bring to his brother. He wanted to give him something special, which would remind him of home. Perhaps some wild artichokes? Meh. Perhaps some wild herbs? Nah. Then it hit him. Since Erzincan was at a much lower elevation than Munzur, it never snowed there. Surely, his brother had to be longing to see snow, and to touch it once again.

The mountain where Belhasan is said to have gathered snow.

Belhasan climbed up into the mountains, to the place that now bears his name, brought down a sackful of snow, and carried it all the way to Erzincan. By the time he offered it to his brother…not a single flake had melted. Tales of the miracle spread far and wide, and when Belhasan died, he was buried at the spot whence he took the snow. In summer, shepherds visit his grave, light candles, sacrifice sheep, and sometimes eat the sacred soil, which is said to have healing powers. These days, however, fewer and fewer people go to this once-important ziyaret, as fewer families migrate up to the highlands.

At the base of the very same mountain sit the sacred springs at El Baba. It’s said that back in the time of Mohammed, an evil ruler had seized a part of Turkey along the Mediterranean Coast. He abducted the most beautiful young women from every village under his control and forced them into his harem. Local people prayed for help, and eventually the army of Ali arrived. A great battle ensued, the wicked ruler was defeated, and the women were freed. One of Ali’s soldiers, however, had been gravely wounded. He had a vision of the springs at El Baba and, convinced that their waters could heal him, set off to find them. According to the story, the soldier died of his injuries just as he reached the springs, but before he could partake of the waters. And that is where he was buried.

Today, people still go to the springs for healing, especially for knee and leg problems; one resident of Guney Konak village said that he was at El Baba when a family arrived with a ten-year-old boy who had never been able to walk; after spending a few hours there, and drinking tea made from a mixture of water and dirt from around the spring, the child got up and walked away with his overjoyed parents, as though his legs had never had a problem!

Perhaps the best-known ziyaret after the source of the Munzur River is a cave in a mountainside near the town of Nazımiye, which is just outside of the Munzur Valley. Known as Düzgün Baba, the story of the holy place once again revolves around a miracle-working shepherd. Some say that if this shepherd, whose name was Haydar, struck a tree with his staff in the middle of winter, fresh green leaves would sprout on its bare branches; if he touched the frozen ground with his staff, fresh green grass would emerge from the snow. Others say that he could make grass grow on a parched and dusty field in the middle of a drought-stricken summer. In either case, he only used his powers secretly, causing his family and friends to wonder how it was possible for his flocks to remain so fat, while theirs were going hungry.

One day, Haydar’s father, Mahmud, decided to spy on his son to see if he could find out what he was doing to keep his herd so healthy. While surreptitiously following Haydar, Mahmud witnessed the miracle and turned to leave. At that very moment, one of Haydar’s goats sneezed, and Haydar said, “What made you sneeze? Did you see my father Mahmud somewhere?” Just then, Haydar caught sight of his father. He was so ashamed at having been heard speaking his father's given name – which, apparently, was considered very disrespectful – that Haydar ran away. In three giant steps, he strode about three miles, leaving impressions of his footprints in the mountains each time, which are still visible today. Upon reaching the cave near Nazimiye, he stopped, and lived there in self-imposed exile for the rest of his life. Occasionally, people went to check on Haydar and, finding that he was alive and well, would report to his parents: “durum düzgündur,“ meaning “everything is fine.” Thus, Haydar became known as Düzgün.

When he died, Düzgün was buried on the ridge above his cave. His grave was marked by a pile of stones, which became an important pilgrimage site. It is said that at one point during Ottoman times, the regional commander of the army, who wanted to deal a blow to the Alevi faithful by dispelling the myth of Düzgün, sent a group of soldiers to dig up the grave, certain there would be no evidence of anyone actually being buried there. But as soon as the soldiers struck the ground with their shovels and picks, a river of blood came pouring out of the earth. The soldiers ran away, terrified. This was irrefutable proof that Düzgün, in fact, was buried there, and the site became even more holy thanks to this miracle that occurred long after his death.

Today, pilgrims tackle a steep and sketchy trail to reach Düzgün Baba. At the cave, people light candles and pray; it’s believed that childless women who go there to ask for a baby will soon become pregnant. Virtually everyone who visits climbs to the back of the cave, where a small hole has been worn in the rock, in which water can be found by those whose souls are pure; spoons are left nearby, with which to scoop and sip the holy liquid.

At the mouth of Düzgün Baba's cave

A father helps his toddler taste the holy water at Düzgün Baba.

Düzgün Baba’s grave

When people in the Munzur region are stricken by a serious illness, such as cancer or kidney failure, they or their family members are likely to head to a peak called Sultan Baba, which rises over the Munzur River as it courses between Ovacik and Tunceli. The top of the mountain is said to be the burial site of a military leader (perhaps Khwarizmshah Jalaluddin) from lands to the east, who managed to escape the onslaught of the Mongol hordes and find refuge in Dersim. Though the story behind Sultan Baba is less clear and less elaborate than the stories of other ziyarets, it remains one of the most sacred sites in the region, where sacrificing sheep has been known to cure even the most intractable maladies.

The ziayarets of Munzur - mountaintops, caves, rivers, rocks, and trees – these are where the Alevis of the valley worship most of the time. But one very important type of ceremony – which revolves around sacred music and ritual dance, and is called a cem – is usually performed indoors.

There's no religious rationale for this choice - it simply happens that most cems are held in winter, when people have more free time, since they are not busy in the fields or up in the mountains with their flocks. In decades past, cems were held in the homes of villagers; today, they are typically held in a cem evi, literally a ‘cem house,’ which is like a community center. Generally of modern cement construction, many cem evis around Munzur have an institutional feel, which the images of Ali and Husayn and other holy men hanging on the walls do little to dispel. The cem itself is performed in a large room, where worshippers sit on a rug-covered floor, facing the pir or pirs who lead the ritual with sermon and song.

Cems have several different components, not all of which are performed at every cem – meaning a ceremony can last from 30 minutes to several hours, depending on how complete it is, and on whether participation is limited to those families who follow a particular pir, or whether the cem is open to all.

Let us explain: Dersim is home to approximately 100 different tribes, about a dozen of which form a priestly caste into which all pirs are born. Known as the ocak, these priestly tribes trace their ancestries back to the family of Ali or other saints. Individuals in the ocak tribes are called seyits. The majority of tribes, which make up the lay community and don’t claim decent from Ali, are called talips (disciples). Every talip family has long-running spiritual ties to a particular ocak family, which typically carries on from generation to generation. Hence, each pir serves a number of talip families in a number of different villages – and his father and grandfather and great-grandfather would have served the very same families in earlier years.

Because one’s connection to one’s teacher is based on age-old family relationships, and this multi-generational relationship is a key part of Kurdish Alevi practice, they generally do not accept converts. Unlike Sufism, which is a mystical religious order that can only be joined by choice – even by children of Sufis – the only way to truly be Alevi is to be born into the faith. Writer's note: Though this seems to be the rule, there is one conspicuous exception: the local Armenian Christians who adopted Alevism. Our understanding is that Armenians married into Alevi families and were thus accepted without the need for an overt conversion, but this may not be true for all Armenians-turned-Alevi. We're simply not sure.

Since every Alevi must have a pir, each ocak family is the disciple of another ocak family; however, rather than creating a vertical hierarchy of priestly tribes, the hierarchy among the ocak is circular: put simply, the seyits from ocak tribe A would the talips of ocak tribe B, the seyits of ocak tribe B would be the talips of ocak tribe C, and the seyits of ocak tribe C would be the talips of ocak tribe A

The pirs – who are also called dedes (meaning 'grandfather') – lead ceremonies and guide their talips along the Alevi path. They also mediate disputes and issue judgments when one person has wronged another. In such cases, the decision of the pir is usually accepted, but if a talip strongly disagrees with his or her pir’s opinion, he or she may appeal to the pir’s pir, who may either uphold or overturn the original ruling.

Pirs are always men, but women from the family of a pir are also highly esteemed. “There are no women dedes because they can’t travel around as easily as the men, and the dedes often need to be away, meeting with talips in distant villages,” says one pir with talips in Guney Konak. “The women always had very important duties of their own, including raising children, and they were respected for that.” Women are sometimes involved in settling disputes, he said, but seem perfectly happy to let the men lead prayer ceremonies, including cems.

A group of pirs in a cem evi.

The daughter of Zeynal Dede

Once the ritual space is ready, the pir plays his baglama and sings about the tragedy of the Battle of Karbala, when Husayn – the son of Ali, grandson of Mohammed, and third Shia imam – was beheaded by his enemies. The rendering of the song is a true art, as the pir’s goal is to evoke a genuine and intense emotional response within the congregation. The effect is quite striking: men and women may weep as though remembering an event that they personally witnessed, rather than something that happened over 1330 years ago, in 680 AD.

The dede’s wife

While the majority of cems these days are open to the general public, participation in the most religiously significant cems is confined to a pir and the talips he serves within one particular tribe. Known as a gurgu cem, this ceremony can only begin when everything is “in the correct way.” The pir questions the congregation, and any conflicts between talips must be resolved before the ritual can proceed. Anything about which a talip feels guilty should also be confessed. Anyone who refuses to put things right, who stays in a state of discord with his or her community, will be excluded from the cem and, depending on the severity of the unresolved issue, may remain something of an outcast until they work things out with the guidance of the pir. The intention behind this practice is not to wield power, instill fear, or dispense punishment, but to create an atmosphere for forgiveness and understanding, clearing the air and bringing the community back into balance with itself.

Once the “people’s court” is over, a few sheep may be brought into the middle of the room. The pir prays over them, and when the sheep stop moving around and stand peacefully, they are then led outside and sacrificed. During the gurgu cem ceremony, young people are initiated into a formal relationship with the pir, while others renew vows to follow the Alevi path.

Among the many variations of cems, a few elements are usually included in all. Typically, men and women sit together on the rug-covered floor, as equals. A sentry guards the door, preventing people from entering or leaving during the ritual. Today, this role is largely ceremonial, but long ago, when Alevis worshipped in secret for fear of being discovered by the authorities, they posted a man as a lookout and a guard, to help protect the worshippers.

As the ceremony begins, a rug is spread for the pir to sit on, or to sit behind, as a sign of respect. Water is sprinkled lightly over members of the congregation, to purify them. Candles are lit, symbolizing the sacred power of fire and the sun. The ground is swept, as a way of clearing out any “bad things” from the room, including negative thoughts.

Women often perform the preparatory rites at the start of a cem.

As the singing begins, the cem evi fills with emotion.

The centerpiece of the cem is the semah – a ritual dance performed by men and women, who whirl and spin together in circular patterns, while the pir plays and sings an Alevi poem or prayer. Often, each dancer holds one hand over his or her heart, while extending the other to the heavens. It’s an exhilarating act of choreographed rapture, which some say represents the dissolution of the individual ego in the living, divine connection between the community and the cosmos. Others say the semah is an expression of the worshippers’ love of God – and of God’s love for them. Yet others say that the dance represents the ability to magically transform into a crane - a bird sacred to Alevis as a symbol of the voice of Ali - and fly.

Following the semah, the candles are extinguished, the pir’s carpet is rolled up, and some food, called lokma, is shared by all – perhaps there's a full meal, including the meat of a sacrificed sheep, or perhaps a few pieces of buttery cake baked in large, shallow, round pans.

Play the video below to see a semah performed in the Munzur Valley:

Some Alevis (mainly the Bektashi) trace the origin of the cem ceremony to the story of the mi’raj – Mohammed’s ascent into heaven. According to the Alevi version of the tale, when the prophet is on his way home after meeting with Allah, he joins a spiritual gathering of a community of enlightened men and women of different ethnic backgrounds, with Ali as their pir. At one point in the evening, everyone, including Mohammed, dances together in a state of ecstasy - which has been reenacted ever since in the semah. Click here to read a re-telling of the Bektashi mi'raj story.

The Alevis of Munzur, however, reject this origin story. “Alevis were making cems long before Mohammed was ever born,” says Hayri Dede – and his claim is echoed by the Zeynal Dede and other knowledgeable Alevi elders in the upper Munzur Valley. The Alevi version of the tale of the mi’raj, they say, was written after Islam swept through the region, and was created to make the cem, and the semah, seem more acceptable to Muslim sensibilities.

If the goal of this tale was to embed ancient Alevi beliefs in an Islamic storyline, merging Alevi principles with Muslim symbology, it was quite successful. Mohammed and Ali are inserted into a scenario that elevates internal truths over external appearances, favors the mystical interpretations over literal ones, and promotes the notion of equality between different races and genders.

If, on the other hand, the aim of rooting the cem in the mi’raj was to make it less outlandish to the majority Sunni community, it didn’t work. To faithful Muslims, the idea of men and women dancing together as a form of worship is simply profane, no matter what “historical” event inspired it

This sentiment reflects the vast difference between Muslim and Alevi attitudes toward women, with Alevis being much more liberal, in ways that are similar to secular Western cultures. In addition to playing an essential role in prayer ceremonies, Alevi women can dress and wear their hair as they please. They can smoke; they can drink; they can get tattoos. Once, when an elderly woman was asked what she thought of her granddaughter’s tattoos, she replied, “Well, I wouldn’t get them, but it’s her body – she can do what she wants with it!” This is not a sentiment that you’d hear expressed in most parts of the Middle East.

Even in Munzur, however, women are subjected to some of the same gender-based double-standards held by many cultures around the world. They fulfill well-defined roles as child-raisers and keepers of the home. Before they are married, girls and women are expected to obey their fathers and to avoid romantic and sexual relationships. Marriage is monogamous, but social status is patrilineal, hence unions between seyit women and talip men may be discouraged by the women’s families, since the children of such a couple would have no claim to their mother’s sacred lineage.

Still, in most ways, women are thought of as equal to men. “Everyone is created by God, everyone is a manifestation of the divine, men and women alike,” says the pir in Guney Konak. Men and women alike follow the same path.

Men and women dance together in groups at weddings.

Men and women pray together in an outdoor ceremony on a sacred hill in the upper Munzur Valley.

One social/religious role played exclusively by men is that of the musahiplik – a special relationship in which two young men who are not blood relatives choose each other to be musahips, or “brothers on the path.” This bond is sealed by a dede, and has profound implications. Musahips are ethically responsible for each other, with each held accountable for the others deeds, as though the two have been fused into a single moral being, each of whom is meant to help the other be the best person he can be.

Musahips are also responsible for each other’s material well-being and, technically speaking, what belongs to one literally belongs to the other. While in the past, musahips may have shared virtually everything, these days they are less likely to do so. But if one needs help, the other readily gives it. Musahips are considered to be so close that, while it’s perfectly normal in Alevi culture for cousins to wed, the children of musahips are absolutely forbidden from marrying each other. They are closer, even, than blood.

Entering into a musahip relationship is considered an important step on the Alevi path – and even though the bond is between two men, women are not left behind. According to Dilsah Deniz, the sacred contract that joins the men is, ideally, “completed with their spouses;” the perfect musahip relationship, thus, actually includes four people. Men must declare a musahip before they get married, as their musahip should accompany them during the ceremony. Once they are both married, the spiritual union of the four is created, and husbands and wives follow the Alevi path together, as equal partners in their journey toward Truth.

Alevism, of course, tends to shun rigid doctrine, so unmarried men and women are not excluded from following the Alevi path; those who remain single are seen as an exception to the general rule, and their marital status does not inhibit their spiritual growth. This is particularly important for women, since single men can still enter into musahip relationships, but women without husbands lack a connection to this auspicious arrangement.

What matters most for any Alevi, man or woman, married or unmarried, is the way they treat other people, and the way they treat the natural world.

For more about the customs, beliefs, and stories of the Munzur Valley, continue to Other Customs.